My sister talks about the pain like she lived through it. She talks about the endless days of finding me screaming out in the middle of the night, on the floor of my bedroom, tears streaming down my face, my body writhing from the excruciating pain of my accident. In some ways I guess she did, I was spoiled rotten and didn’t make the months it took me to recuperate easy for everyone around me. I blamed them even though they had nothing to do with it, and so tried to make sure they at least felt a small part of my misery.

I was twelve when it happened, way too old for my skin to ever recover properly from the accident, and so it left me with horrible scars on both my legs, the entire expanse of the skin covering them looked like paper that had been crumpled up and never quite straightened back properly. Angry black marks where an iron bed bunk had collapsed on my legs in the fire, were left slashed across both my “oyibo” thighs and legs, like a child had drawn them on.

At twelve I was the queen of shakara, I lived for miniskirts, and bags and shoes that looked as grown up as I could manage. My mother was the first to suggest I stop wearing the miniskirts after the accident. She explained that people would make me feel sad when they saw my scars.

I didn’t understand what she meant by this, was it somehow my fault that I had gotten those scars? Why would people make me feel sad about them, was I a bad person? Was that why I got caught in the fire?

She got several new pairs of my school uniform made for me, and made the pleated skirts as long as she could when I was declared fit enough to go back to school. I hated them on sight, and put up a fight the morning of my first day back. She put her foot down and I went to school at the brink of tears, by my third period I had finally succumbed to the tears and was holed up in the girl’s bathroom. But it wasn’t because of my ugly skirt. I wished fervently then that the skirt would become long enough to cover my ankles, so I wouldn’t have to face the ehyas and the peles. So I wouldn’t have to see the looks of pity in the eyes of my friends, looks that made me feel like I was somehow deformed because of my scars.

My mother was sent for, and I took the rest of the day off school. I embraced my long skirts after then and made my mother buy socks that went up to my underwear to hide what parts of my leg the skirts didn’t cover.

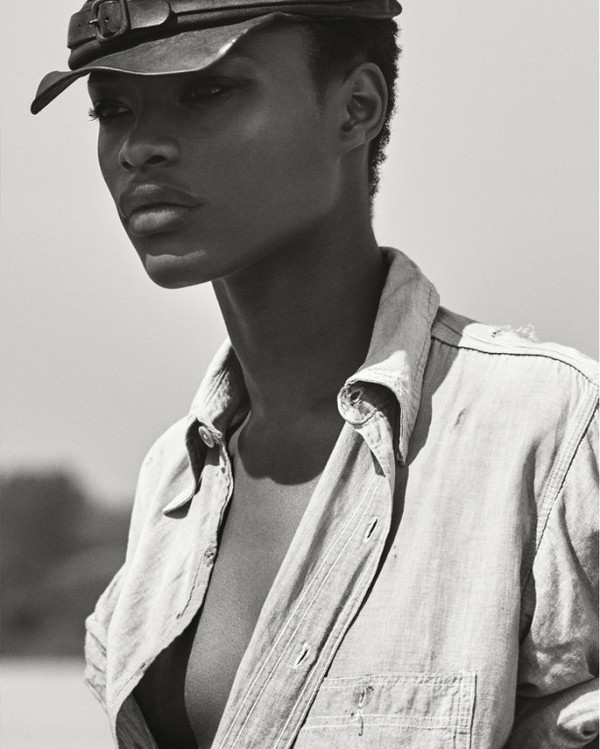

After secondary school, it was easy to hide my scars. I owned only jeans and maxis, and never put myself in a position where I had to show of my legs, like going swimming in public. It’s 2016 now and I see so many brave women on the internet embracing scars that have become part of them, showing them off proudly like a badge of honour. I now know that they are not a deformity, that they are a sign that I am strong and I survived what could have easily been a terrible fate, that they are the battle scars I had gotten from my fight with death and I had won the battle.

I haven’t gotten to a point where I could confidently strut around in a bikini in public, but the hemline of my skirts are finally inching back up.